A Deep Dive Into the Spacing Effect

Jonathan Firth's Memory & Metacognition Updates #39

Today’s focus is the spacing effect. Although I have mentioned it a few times (for example in my summary of Dunlosky et al’s list of strategies here), I haven’t previously focused a whole update on the topic. So, here goes!

The spacing effect (aka distributed practice) is really useful and applicable. It was one of the first areas of memory research that I explored, partly because it’s so easy to connect it to teaching.

It feels like an easy win. All you need to do is change the timing of when you do something (delaying the practice), and students learn better. What is there to lose?!

The Basics

The basic idea behind the spacing effect is that if we delay practice, it is more effective. To put it another way, a period of forgetting before further practice makes learning more effective. Forgetting can be useful!

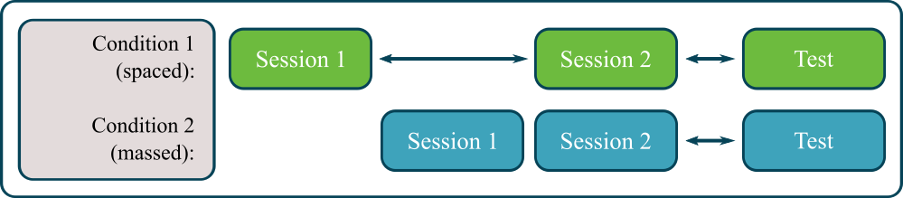

The following diagram shows the design of a typical experiment into the spacing effect:

Again and again, research has found spaced practice is more effective than massed practice (Dempster, 1988). It’s a phenomenon that has been documented for over 100 years.

Applying the Effect

Imagine that you (or your students) were going to spend an hour practising a particular skill. The spacing effect suggests that it would be more effective to practise for half an hour today and another half an hour tomorrow (the green boxes above), rather than the whole hour as a single session (the turquoise boxes above).

It’s important that the students really learn something in that initial practice session, however. There is no point in stopping before they have understood new knowledge or got the hang of a skill.

But once they have reached mastery, further practice could be a waste of time. It would be best to wait – with a longer gap preferable to a shorter one.

Some researchers have suggested that the best schedule overall is practising until students have got things right three times in quick succession (within a single lesson/session), and then three further times at widely spaced intervals (Rawson & Dunlosky, 2011).

Breadth of the Idea

One of the great things about the spacing effect is that anything can be spaced. This makes the effect incredibly handy and flexible.

Often, you don’t actually have to change what you are doing, either—just do it at a different time (as I discuss here). For example, rather than summarise or hold a plenary at the end of today’s lesson, you could do it at the beginning of next week’s. And rather than set homework on a topic straight away, you could delay it by a week or two.

Desirable Difficulties

It’s worth bearing in mind that spacing out practice makes it harder. After a delay, students will find learning more effortful, and they’ll make more mistakes. In short, it’s a desirable difficulty. It makes learning harder, but in a good way, improving attainment in the long run.

This is not intuitive, however. Teachers and students tend to avoid spacing out their practice, incorrectly believing that it makes sense to consolidate learning as soon as possible.

You may find these misconceptions among your own colleagues and students. Below is a short piece on spacing/distributed practice you could share (free to access):

Distributed Practice. Or: the spacing effect. In a nutshell.

EduTwitter Chat

This week on Twitter, my department – account @StrathEDU – are holding a live chat about research-informed teaching. The questions are below. It takes place at 16:30 BST (one hour ahead of UTC) on Thursday 27th, but feel free to chip in any time with your thoughts, using the hashtag #StrathEduChat.

Questions below:

And here’s the link to the PSHE event I mentioned last time: Personal, Social and Health Education Network: Working Together to Improve Health & Wellbeing.

Have a great week!

Jonathan

Last week: Memory & Metacognition Updates – A Year Later

Website: www.jonathanfirth.co.uk